35 years of the Anarchist Federation – reflections on 1986 and now

Original article published in Organise! issue 94, Spring 2021, magazine of the Anarchist Federation (Britain): http://afed.org.uk/organise-magazine-issue-94-spring-2021/

It’s 35 years since the AF was first formed as the Anarchist Communist Federation in 1986. We’ve published retrospectives on several occasions before in the 10, 20, 25 and 30 year specials of Organise! This time we look back at what was happening in and around 1986 and its relationship to the emergence of the new anarchist organisations.

1986 had seen in some big anarchist anniversaries of its own. As well as the year being the centenary of the Haymarket Affair of 4th May 1886 in Chicago and a half century since the start of the Spanish Revolution in 1936, anarcho-pacifist influenced paper Peace News celebrated 50, and ‘Freedom / A Hundred Years’, a special centenary journal, was published. However, the views of those attached to Freedom at the time were not widely embraced by the emerging class struggle anarchist current. Although there was reference to history of the movement, including names associated with the origins of anarchist communism, much of the contemporary opinion read as of out-of-touch reminiscence and philosophical pondering, especially after the Miners’ strike battles and ‘inner city riots’ of the early decade. One article from a member of the newly launched Class War Federation did put the case for class politics and meaningful direct action (and appealed for anarchists to break from punk and veganism.) The article also called for more anarchist organisation and applauded the formation of the ACF.

Cold War politics

American militarism was a major 1980s political theme. The Ronald Reagan presidency was engaged in a not-so-Cold War in many corners of the globe. The US government was supporting several right-wing governments and insurgencies in Central America, including what became the Iran-Contra Affair, where the National Security Council was found to be covertly selling arms to Iran and using proceeds from this to fund right-wing rebel militias in Nicaragua. The Central Intelligence Agency was supporting Islamic fighters ‘Mujahideen’ in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union and UNITA in Angola who were a major ally of the South African state. Whilst Chomsky and Herman’s book ‘Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media’ (1988) was around the corner, anarchists were stressing the need for Do-It-Yourself publishing by revolutionaries.

In the last few years before the Berlin Wall was brought down, when the dual influences of Soviet Union and USA still divided up the globe, understanding of geo-politics was prevalent amongst the Left in Britain. The UK establishment’s role in supporting the Chilean junta had been a major Trade Union issue and so earlier in the 1980s it was especially galling to see the government cosy up to Pinochet and resume arms sales. The Falklands War was judged by the Left to be British jingoism and a key part of the election campaign tool for the Thatcher second term. The Anti-Apartheid Movement was strong and the Conservative Right’s support for the regime was well known. Around 1986, the Federation of Conservative Students was making a nuisance of itself with a universities speaking tour of Monday Club members and other politicians well known for their support for white power in South Africa and Rhodesia (pre-Zimbabwe) and anti-immigration policies and views. This led to a great deal of direct action that was supported by anarchists, to oppose and ‘no-platform’ specifically racist individuals.

In the UK, a major focus of direct action in addition to big demonstrations was against US military power more broadly. Reagan was engaged in brinkmanship with the waning Soviet power and had bought Cruise Missiles to air bases in England with the support of the Conservatives. Anarchists were active on CND demonstrations and set up peace camps. Involvement in direct action, including a great deal of fence cutting at Greenham Common, Molesworth and other USAF bases, led to important discussions in the peace movement about ‘violence to property’ that was eventually resolved in anarchist circles even amongst pacifists (where the consensus became that destruction of property was not considered to be violence.) Class struggle anarchism was, however, beginning to critique the peace movement as lifestylist, something that was also directed at Green Anarchist, its paper being quite visible on Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament demos. Also, anarchists, unlike some on the Left, were accepting of separatism in the movement (a defining feature of the Greenham women’s camps) and the ACF reflected this in its aims and principles, whilst in practice the mainly mixed anarchist groups assumed men within them were feminist anyway.

Thatcher, Thatcher …

1986 was past mid-way of Thatcher’s second term as Prime Minister and the neoliberal project was in full swing. Utilities and the buses were being privatised, and a law was passed to de-mutualise Building Societies. The year also saw the ‘Big Bang’ deregulation of the City allowing vast sums to be made from the easy credit available resulting in massive debt for many of the working class. The year also continued the cheap sell-off of council housing under ‘Right to Buy’ with discounts of up to 70% available for aspiring home-owners. Land and property prices were about to boom leading to gentrification becoming a major feature of Southern big cities whilst the Tories seemed content to let the North suffer the rot of industrial decay. Unemployment was stuck at over 3 million. Bradford’s ‘1 in 12 Club’ launch was one early anarchist recognition of the need for more autonomous spaces in the anarchist movement, whose name comes directly out of the unemployment statistics of the time. In general, anarchists were heavily involved with mutual aid in the face of Thatcherite attacks on welfare. Other important activist spaces such as the Autonomous Centre of Edinburgh had begun as advice centres.

The Marxist-Leninist/Trotskyist left was reeling since the second Thatcher election victory. Neil Kinnock, Labour leader, was spending much time in power marginalising them. Derek Hatton, deputy leader of Liverpool City Council was thrown out of the Party for his membership of the Militant Tendency. Along with various other city councils Liverpool he played a major part in the Militant inspired rate-capping rebellion against Thatcher’s plans to squeeze local government finances. Also in 1986, the GLC, led by Ken Livingstone and John McDonnell (known more recently as Corbyn’s Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer) was abolished, weakening the Left’s control of London. These events of the mid-80s represented the death-throws of Old Labour. The Local Government Act that was associated with rate-setting mentioned above was passed in 1986. This was notoriously amended in 1988 to add the Clause/Section 28 “prohibit the promotion of homosexuality by local authorities” which had not made it into the Act two years earlier. Anarchists took part in the many Clause 28 protests; it was eventually repealed in 2003.

In January 1986, the major labour movement struggle since the end of the Miners’ Strike was about to begin; the year-long Wapping Dispute. Rupert Murdoch’s News International empire was in the process of moving the Sun, Times and associated Sunday newspapers away from their long-time home on Fleet Street. A major part of the modernisation plan was to destroy the print unions’ power by sacking most of the no-longer needed typesetters and ensuring non-closed shop contracts at the new plant at Wapping. There was strong critique amongst class struggle anarchists and anarcho-syndicalists of the Trade Unions inability to foster solidarity. The campaign to support the printers from anarchists included supporting weekly demonstrations outside the Wapping plant and direct action to prevent distribution of papers by private haulage company TNT. The demos were heavily and violently policed with running battles most weeks. This dispute further consolidated the anarchist organisations attitude to the police as front-line enemies and towards class violence. The government upped the ante with the passing of the Public Order Act (1986) which gave police powers to control “public processions and assemblies” and provided long maximum sentences for riot, violent disorder and affray (10, 5 and 3 years) that were used to great effect by the state in the anti-Poll Tax campaign a few years later (anarchists responded to the “Battle of Trafalgar” of March 1990 by initiating unconditional legal support for the hundreds arrested).

Our movement in 2021

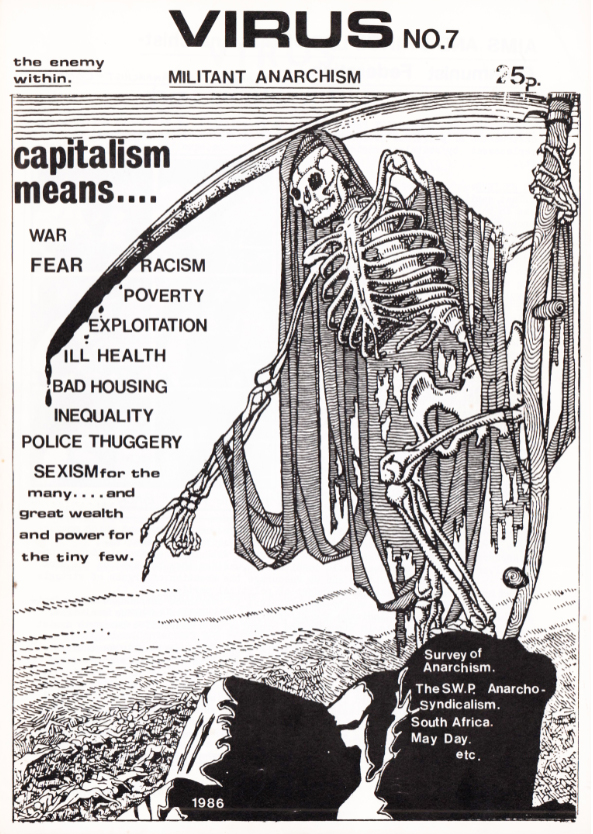

So where are we in 2021? In 1986 the anarchist papers like Virus (forerunner of Organise!), Class War and Direct Action fed on the anger of the middle Thatcher years and looked to working class revolt for inspiration. The pages of these papers would also go on to cover in some detail developments in Northern Ireland that followed the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement with some anarchists verging on support for the nationalist cause as a reflection of the anti-imperialism that was still very prevalent on the Left. There is now a more critical eye on colonialism that could perhaps help steer a better path between ultraleft and anti-imperialist positions such as in the analysis of Rojava where there is much disagreement amongst anarchists. As well as coming from the trigger of Brexit, the April 2021 rioting in Northern Ireland has its origins in the history of the Union and struggle for a United Ireland that anarchists were aiming to make sense of in their papers in the 1980s, but are less vocal about since the ending of the Troubles.

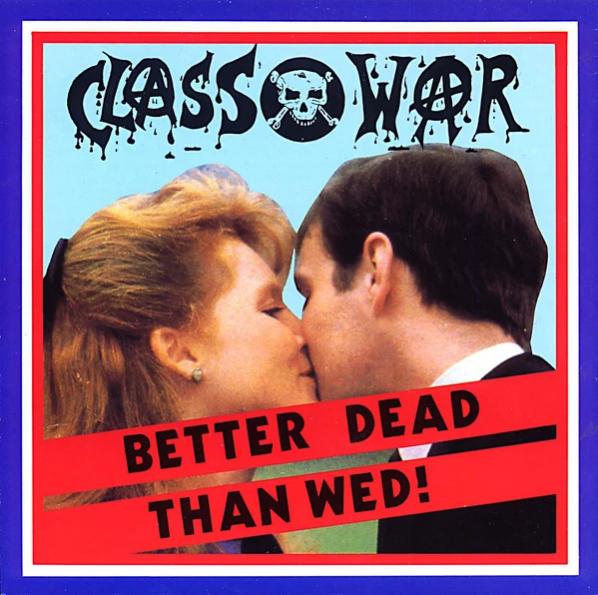

The family occasions of the Royals were a source of derision amongst many anarchists in the 1980s, especially for Class War, who produced the single ‘Better Dead than Wed!’ in response to the marriage of Andrew and Fergie. But with both The Windsors and The Crown as entertainment on Netflix and their real lives even stranger than fiction it hardly seems necessary for anarchists to make much effort ridiculing them anymore.

The mainstream media news has been very much about Party politics, and, until the pandemic hit, Brexit dominated the political agenda and to a lesser extent Scottish Independence. But anarchists were neither pro- nor anti-Brexit, treating Fortress Europe and English nationalism as two sides of a statist and capitalist coin. We were also mostly disinterested in the tussles within and between parties on either side of the border. The rise and fall of Corbyn and the installation of a ‘safe pair of hands’ like Keir Starmer sometimes feels a bit like the Kinnock years as the Labour Party tries once again to regain electoral credibility; this holds little appeal to anarchists apart from to say “told you so” to those leftists who spent time canvassing for Corbyn.

The last few years have not been kind to grassroots politics either, though. Our DIY press is no longer special, being just one drop in a vast ocean of internet media that is directed to individuals’ computer and phones by algorithms, whilst each populist state leader has been amongst the mainstream media’s biggest critics as a technique to position them alone as the “voice of the people”. Anarchists are also now having to explicitly distance ourselves from conspiracy theorists and be more nuanced about saying all politicians are liars. A lot of the community work nowadays is defensive, running first food banks and then soup kitchens as more people have struggled to feed themselves after incomes from low paid and precarious work evaporated during the pandemic. Anarchists have played a small part in this widespread need for mutual aid with good examples in London (GAF free shops) and Bristol (BASE & Roses).

One element of déjà vu from 1986 comes from the announcement of a new ‘Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill.’ Judging by the use of police powers granted during the pandemic, this is more likely to be directed at stifling Reclaim These Streets protests against violence to women, Black Lives Matter demos and Extinction Rebellion actions, or as yet another attack on travellers, rather than being used to control workers disputes or demos about global politics. This said, economic strife may be around the corner as the state claws back the billions spent during the pandemic. A class analysis is essential as the outcome of the pandemic will amplify inequalities as much as the pandemic itself has revealed them. Anarchists also have much to offer tactically and have been instrumental in providing legal support on recent demos, which is an important legacy of the knowledge sharing and organisation of defence groups following the Public Order Act of 1986. The debate about violence to property has come back though in the context of statue toppling; anarchists could usefully look to the 1980s to see how this was justified in Peace News.

Globalisation

Internationally, things are very different in the organised anarchist movement since 1986. The Cold War framing of Latin American politics shifted after the fall of the Berlin Wall in the 1990s to a critique of capitalist globalisation. In Mexico, the Zapatistas emerged as a force in direct response to the North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994, which brought anarchism into direct solidarity relationships with indigenous struggles with support of many anarchists in Britain and Ireland for the Encuentros in Chiapas and other solidarity activity with comrades from Oaxaca and members of the FAM (Federación Anarquista de México) that AF was involved with. Anti-capitalism became a central feature of anarchist involvement in struggles of the 2000s, its forerunners existing in the Stop the City actions of the 1980s against the military-industrial complex, but now even more explicitly transnationalist with a No Borders ethos. For the AF, our international links have continued to grow since our joining the International of Anarchist Federations in 2000. Organisations in IFA include the Czech and Slovak Anarchist Federation and Federation of Anarchist Organising in Slovenia & Croatia, and we have good contact with comrades from Belarus who face intense and continued repression. Links with anarchists in the East, and most of the organisations themselves, simply did not exist or were still in exile in the West in the early-to-mid 1980s due to the Iron Curtain. The Latin American federations in IFA are highlighting the ongoing need for support for indigenous struggles, including the Mapuche people facing modern day land-grabs by corporations in Chile, and the massively unequal effect of Coronavirus amidst the contempt of Brazilian leader Bolsonaro for indigenous communities. This is in addition to the stark differences in access to vaccination between the richer and poorer countries in our international.

The rifts in British anarchist, feminist and left movements, caused by a reactionary rise in transphobia, had meant the postponement of larger anarchist events that have not yet returned due to the pandemic, although an online ‘Anarchist Bookfair in London’ was successfully held last year. The consultation on amendment of the Gender Recognition Act in UK and the activism of trans people, including those in AF, to increase visibility and acceptance, had put a small powerful group of ex-feminist academics and journalists in an uneasy alliance with religious fundamentalists, social conservatives and the far right. The antagonism is a departure from the 1980s when left and right politics were more clearly defined and anarchists aligned with the feminist movement for the most part, where the negatives focussed mainly on critiques of reformism or cross-class alliances. This has all caused headaches for some anarchists. Echoes of ‘no-platform’ were heard before the pandemic but the more confrontational face-to-face meetings have stopped due to social distancing, whilst the government decision not to amend the GRA to allow self-determination has fulfilled some of the reactionaries’ aims. The fight for transgender equality is ongoing and strongly reflects that against homophobia in the 1980s. The AF itself moved some years ago to the recognition of internal oppressions with the formalising of caususes that meet and organise separately whilst 2020s anarcha-feminism is confident in defining its own parameters.

Hopefully, the message of the class struggle anarchists of 1986 still stands regarding the need for organisations. A libertarian perspective will be needed to critique Coronavirus Passports which may otherwise realise the introduction ‘ID cards’ (proposed by successive government both Tory and Labour since the 1980s for other reasons) and to keep up the pressure that will hopefully Kill the Bill. Good organisation is needed, especially during the pandemic when we are more physically isolated, to make the case for an anarchist communist perspective.■